Articles

-

Employment Law

Employment LawSocial Media and Personal Behavior: What Can Get You Fired?

-

Family Law

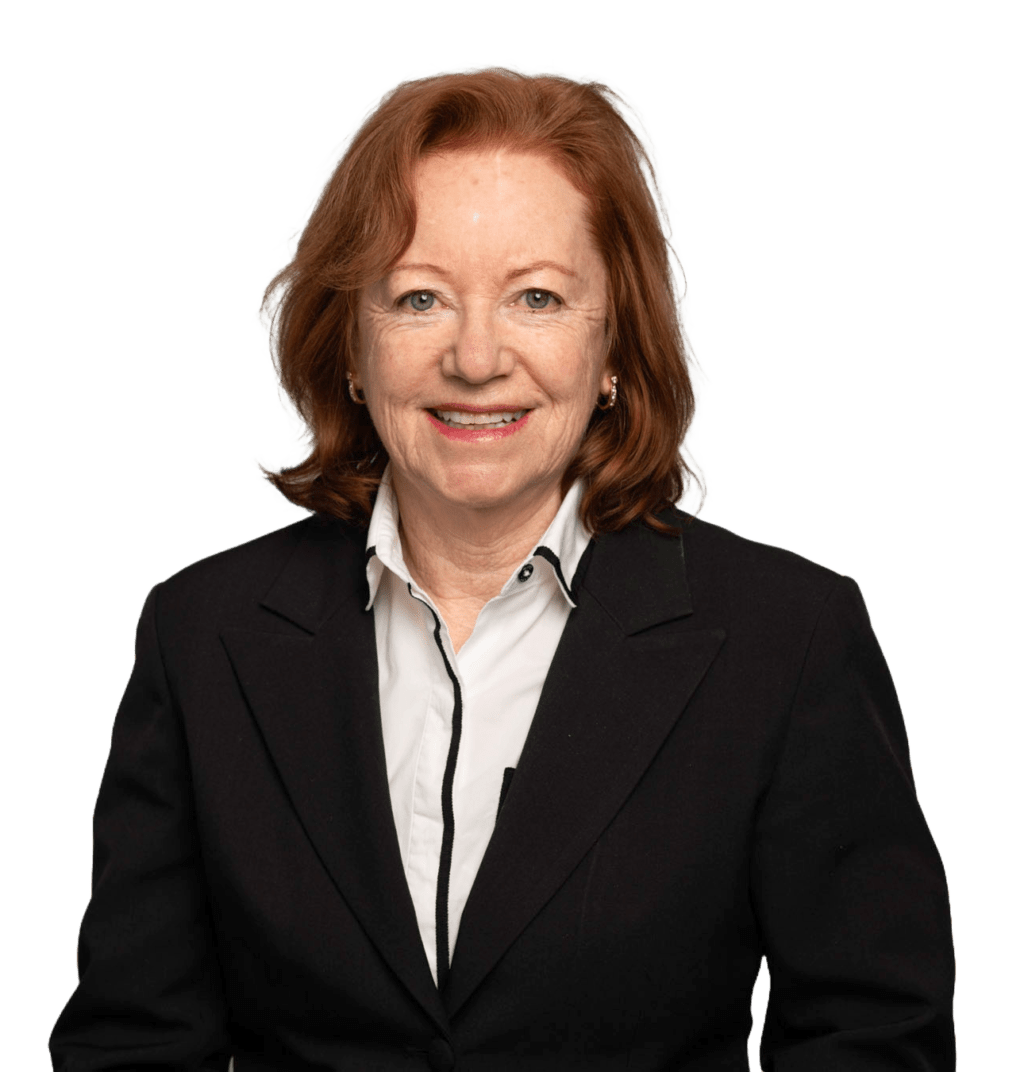

Family LawPenny Paul of Anderson Paul joins Mackoff Mohamed

-

Employment Law

Employment LawPay Transparency in British Columbia

-

Personal Injury

Personal InjuryThe decision in Symons v. Insurance Corporation of British Columbia, 2016 BCCA – Summary and Implication

-

Employment Law

Employment LawImplications of Promotion May Invalidate Employment Contract

-

Civil Litigation

Civil LitigationWhen are Children’s Household Chores Compensable?

-

Civil Litigation

Civil LitigationUnderstanding a Certificate of Pending Litigation

-

Product Liability

Product LiabilitySelf-Driving Vehicles: Legal Considerations and the Future

-

Personal Injury

Personal InjuryFelix v. Insurance Corporation of British Columbia, 2015 BCCA 394: The decision and its implications

-

Uncategorized

UncategorizedCan you hold your phone while driving?

-

Employment Law

Employment LawCompeting with non-competes

-

Product Liability

Product LiabilityProduct Liability Claim in Richmond Review and The Province